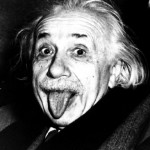

Reflecting upon his scientific achievements, Albert Einstein once noted: “I sometimes ask myself . . . how did it come that I was the one to develop the theory of relativity? The reason, I think, is that a normal adult never stops to think about problems of space and time. These are things which he has thought of as a child. But my intellectual development was retarded, [italics mine] as a result of which I began to wonder about space and time only when I had already grown up.” (quoted in Einstein: The Life and Times by Ronald Clark, p. 27).

Reflecting upon his scientific achievements, Albert Einstein once noted: “I sometimes ask myself . . . how did it come that I was the one to develop the theory of relativity? The reason, I think, is that a normal adult never stops to think about problems of space and time. These are things which he has thought of as a child. But my intellectual development was retarded, [italics mine] as a result of which I began to wonder about space and time only when I had already grown up.” (quoted in Einstein: The Life and Times by Ronald Clark, p. 27).

Einstein “intellectually retarded”? What he was referring to is neoteny (Latin for “holding youth”), a concept in developmental biology that refers to the retention of childlike characteristics into adulthood. One of the best books on this subject is Ashley Montagu‘s Growing Young.

In the first half of the book, Montagu describes biological neoteny; how, for example, two traits – the rounded forehead and chin of an infant ape – are “lost” as that ape grows into maturity (in the adult ape, the forehead recedes and the chin juts out sharply). In this case, there is no neoteny – these youthful characteristics are not retained into maturity. But with homo sapiens, the rounded forehead and chin of an infant child are retained into adulthood. The adult may have gray hair, wear eyeglasses, and develop jowels, but those two infantile traits of chin-ness and forehead-ness have been largely preserved. In this case, there is neoteny: these two youthful traits have been retained into maturity.

The great evolutionary thinker Stephen Jay Gould believed that human beings are just neoteous apes; in other words, the youthful characteristics of apes have, in the course of evolution, simply been held into adulthood in human beings. According to Gould, this is the most important determination of human evolution (see his book Ontology and Phylogeny).

It was neoteny, for example, that slowed down the development of the human brain after birth so that it could continue to grow and develop in relationship to the specific environmental conditions around it. This brain neoteny conferred an incredible capacity for adaptability onto humans, leading to increased chances for survival and the passing on of “neotenous genes.”

In the second half of Ashley Montagu’s book, he talks specifically about psychological neoteny. He examines several psychological traits of children – playfulness, curiosity, humor, creativity, sensitivity, and wonder, among many others – and suggests that these are also traits that need to be retained into adulthood (I have also explored the importance of retaining these childlike traits into adulthood in my book Awakening Genius in the Classroom).

What happens, for example, if the flexibility of childhood is lost in adulthood? Then you have a situation where the world is full of inflexible adults. Consider that some of these inflexible adults have their fingers on nuclear buttons around the world and are involved in major global disputes.

You can begin to appreciate how the presence or absence of the childlike trait of flexibility may make all the difference between our species continuing to survive, or alternatively, our species blowing itself up in a nuclear war and becoming extinct. Similarly, what happens when curiosity or creativity are lost as the child becomes an adult? Then we develop a culture that cannot continue to adapt to changing conditions.

Fortunately, our species seems to retain these psychological youthful traits in at least some of its members; mostly, it seems, in creative artists, inventors, musicians, entrepreneurs, and other innovators of society. Look, for example, at the boyish qualities and childlike enthusiasm of Bill Gates – there’s a case of neoteny that has had a profound influence on technology.

Other examples of neotenous individuals might include Pablo Picasso, Ludwig van Beethoven, Isaac Newton (who said he felt like a child on the beach playing with ideas as if they were beautiful seashells), William Shakespeare (whose bawdy puns and insults offended the non-neotenous critics of his day) and many others. It deserves mentioning here that the concept of neoteny puts a bit of a crimp in the concept of “immaturity” in psychiatry and psychology. It turns out that being immature may not be such a bad thing after all!

For a self-help book based on neoteny called You’re Only Young Twice, by Ronda Beaman, click here.

For more on issues related to human development, see Thomas Armstrong, The Human Odyssey: Navigating the Twelve Stages of Life

This article was brought to you by Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D. and www.institute4learning.com.

Follow me on Twitter: @Dr_Armstrong