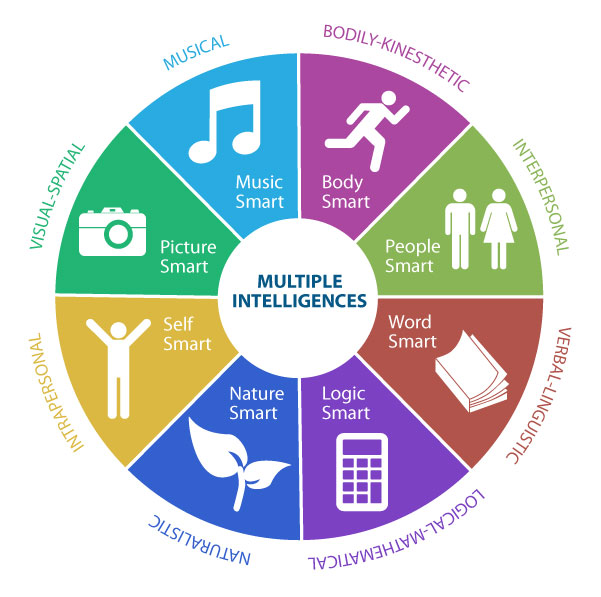

Anyone who has been in American education for more than a generation understands that educational trends come in waves. Progressive education gives way to back to basics which yields to open education which in term is supplanted by cultural literacy, high stakes testing and standards-based instruction. And so it goes. Somewhere in there, around about the middle of the 1990’s and extending for several years, multiple intelligences was all the rage. Originally developed by Harvard professor Howard Gardner in 1983, MI theory (as it was sometimes called), argued that the singular concept of intelligence as measured by an I.Q. score was far too limited a way to account for the breadth of human potential. Gardner’s theory suggested that there were at least seven intelligences, including linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal (Gardner added the naturalist intelligence as an eighth intelligence in 1995). This model became the basis for widespread educational innovation in the United States extending from the classroom level, where teachers sought to craft lesson plans that taught academic skills using the eight intelligences, to the school level where principals offered expanded course work to cover all eight intelligences (with a greater emphasis on the arts), to the state level, where administrators made multiple intelligences a top priority in allocating funds for professional development and school improvement.

Anyone who has been in American education for more than a generation understands that educational trends come in waves. Progressive education gives way to back to basics which yields to open education which in term is supplanted by cultural literacy, high stakes testing and standards-based instruction. And so it goes. Somewhere in there, around about the middle of the 1990’s and extending for several years, multiple intelligences was all the rage. Originally developed by Harvard professor Howard Gardner in 1983, MI theory (as it was sometimes called), argued that the singular concept of intelligence as measured by an I.Q. score was far too limited a way to account for the breadth of human potential. Gardner’s theory suggested that there were at least seven intelligences, including linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal (Gardner added the naturalist intelligence as an eighth intelligence in 1995). This model became the basis for widespread educational innovation in the United States extending from the classroom level, where teachers sought to craft lesson plans that taught academic skills using the eight intelligences, to the school level where principals offered expanded course work to cover all eight intelligences (with a greater emphasis on the arts), to the state level, where administrators made multiple intelligences a top priority in allocating funds for professional development and school improvement.

Then everything changed. My wake-up call to this new trend came when I was speaking on the phone to an official of the American Federation of Teachers in 2005 about my coming to deliver a workshop to their teachers at a conference in Washington, D.C. I had been giving multiple intelligences workshops since 1986, but also spoke on other themes, and when the official started suggesting several of these other topics, I asked her ‘’I’m interested why you haven’t mentioned multiple intelligences as a possibility.’’ She responded: ‘’multiple intelligences isn’t evidence-based.’’ Kazow! It wasn’t long before my own workshops on the subject went into decline. Around this same time, a number of cognitive psychologists and psychometricians began pitching salvos in journal articles against multiple intelligences, often asserting that there was little evidence that MI theory improved school achievement.

Now this decline and fall of MI theory makes sense to me. For the past thirty-five years, largely as a result of the machinations of politicians, CEOs of large corporations, and school bureaucrats, an educational system has been set in place in the United States that emphasizes skill-based standards and high-stakes tests. When the No Child Left Behind law was signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2002, it included the stipulation that educational interventions being used to improve student achievement had to be ‘’scientifically-based.’’ This usually meant the implementation of a research protocol that compared a group of students who had been exposed to a given teaching intervention with a matched control group using a pre-test/post-test format. The ‘’statistic of choice’’ used to evaluate the differences between the groups was the ‘’effect size’’ representing the differences in the mean of the two groups’ performance divided by the standard deviation, a measure which allowed researchers to examine ‘’real’’ differences between groups and also allowed for ‘’meta-analysis’’ a method that pooled several studies into one large group.

Led by researchers such as American educator Robert Marzano (co-author of Classroom Instruction that Works) and Australian educator John Hattie (author of Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement), teachers and administrators flocked to teaching strategies that had the best ‘’effect sizes.’’ Hattie’s book, in particular, went hog wild toward this approach to teaching effectiveness. In Visible Learning he included what he called ‘’barometers of influence’’ which were speedometer-looking graphics where an arrow pointed along a semi-circle to a given effect size between -0.2 (negative impact) and 1.2 (very positive impact). A 0.4 effect-size seemed to be the breaking point between an effective teaching intervention and one that didn’t measure up. The specificity of the measure seemed to meet the needs of educators who wanted to know whether direct instruction, for example, was all it was cracked up to be or, if peer-teaching was instead a better way to go.

Somehow in all this new focus on scientifically-based teaching strategies (also referred to as ‘’evidence-based’’ or ‘’research-based’’ instruction), multiple intelligences was nowhere to be seen. This was understandable since any effort to design a randomized controlled trial of MI theory would have been futile in any case. This is because multiple intelligences is not a teaching strategy in the same way that, say, providing feedback, is an intervention. Multiple intelligences is a theory of how the mind works and an educational philosophy that applies this cognitive model to the idea that instruction should be delivered in a multiplicity of ways to a diverse learner population. How could one possibly construct a research protocol where ‘’multiple intelligences’’ was the ‘’intervention’’ used in one group, while a control group received no ‘’multiple intelligences intervention’’? Multiple intelligences includes potentially thousands of strategies, some of which have been empirically verified in the way described above. Marzano, for example, lists ‘’cooperative learning’’ and ‘’nonlinguistic representation” as solid research based strategies, each of which is or should be a regular part of any good multiple intelligences-based classroom.

Perhaps what riles me most about the idea that multiple intelligences isn’t ‘’research-based’’ is that it implies research results must be limited to standardized tests and statistical analysis. In truth, multiple intelligences is the solidest research-based theory that education has ever had, if you count as research: neuroscience studies, anthropological findings, semiotic research (intelligences have different representational systems), animal studies, cognitive archeology (the presence of the eight intelligences are suggested in archeological digs), and abnormal and developmental psychology (highlighting the life trajectories of noted individuals as well as savants). The fact that these disciplines do not typically generate ‘’effect sizes’’ does not diminish their power one bit. Instead, results are expressed in fMRI data, individual case studies, field studies, content analysis and other largely non-statistical measures. In their rejection of multiple intelligences, educators should ask themselves to what extent education has been overcome by a positivist epidemic that embraces scientism (an excessive belief in the explanatory power of science). We are, after all, concerned with real children’s lives in the classroom, their hopes, dreams, fears, and challenges as well as their complex minds. Wouldn’t a cognitive-humanistic approach to instruction (embraced by multiple intelligences) be truer to the students we serve?

For more on multiple intelligences and its critics, see my new edition of Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom (ASCD).

This article was brought to you by Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D. and www.institute4learning.com

Follow me on Twitter: @Dr_Armstrong