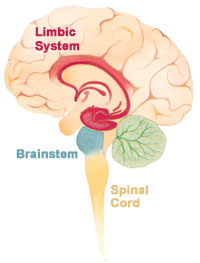

A new study published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry revealed that certain subcortical structures in the brains of individuals diagnosed with ADHD are smaller in volume than typically developing matched controls (the median age of the 1713 participants diagnosed with ADHD was 14). The specific structures where differences were found included the nucleus accumbens, the amygdala, the caudate nucleus, the hippocampus, and the putamen. These structures are important for, among other things, memory, cognition, emotional expression, sensitivity to rewards, and motor activity. This study complements other studies which have shown less volume in regions of the cerebral cortex among children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD.

A new study published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry revealed that certain subcortical structures in the brains of individuals diagnosed with ADHD are smaller in volume than typically developing matched controls (the median age of the 1713 participants diagnosed with ADHD was 14). The specific structures where differences were found included the nucleus accumbens, the amygdala, the caudate nucleus, the hippocampus, and the putamen. These structures are important for, among other things, memory, cognition, emotional expression, sensitivity to rewards, and motor activity. This study complements other studies which have shown less volume in regions of the cerebral cortex among children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD.

“We hope that this will help to reduce stigma that ADHD is ‘just a label’ for difficult children or caused by poor parenting. This is definitely not the case, and we hope that this work will contribute to a better understanding of the disorder,” principal investigator of the Lancet Psychiatry study Martine Hoogman, PhD, of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in statement that was reported in an article on this research published in Medscape. Interestingly, the Medscape article was titled: Confirmed: ADHD Brain is Different [italics mine]. In an abstract of the study, the investigators wrote: ”We extend the brain maturation delay theory for ADHD to include subcortical structures.” [italics mine]

So we’re left with the question: is ADHD a disorder, a difference, or a delay? I believe that the delay hypothesis is the best of the three interpretations. First, other studies (noted above) have shown cortical delays among children and adolescence diagnosed with ADHD. Second, longitudinal studies of ADHD suggest that the incidence of the disorder drops significantly as the individual grows from childhood to adulthood. Third, anyone who has had direct experience of kids diagnosed with ADHD will recognize that many of these children act younger than their years. Fourth, the Lancet Psychiatry study itself said ”Exploratory lifespan modelling suggested a delay of maturation.”

So are these kids then just immature? Perhaps. But I believe that the word ”immature” has a negative connotation that is not helpful in understanding the nature of the diagnosis. A better word would be ”neotenous”. Neoteny is a word drawn from developmental biology, which is Latin for ”holding youth.” A person who is neotenous acts younger than their years. Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould has written that neoteny may be the single most important feature in the evolution of human beings because it translates to flexibility (the immature cortex has time during the first few years of life to adapt to whatever stimuli are in its surroundings, which gives it clear adaptive advantages over organisms that are hardwired at birth or shortly thereafter to respond in a fixed way to their environment). Interestingly, many great thinkers have shown neotenous traits (Einstein said himself, that his growth was ”retarded” so that he thought like a child when he was an adult: ”My intellectual development was retarded, as a result of which I began to wonder about space and time only when I had already grown up.” (quoted in Ronald Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times, New York: William Morrow, 2007, p. 27).

Consequently, people need to be careful when they read about this study and others like it, not to conclude (as apparently one of the investigators did) that this is confirmation that ADHD is a neurologic disorder. The ”disorder” paradigm simply feeds into negative expectations for these kids, and also validates the use of psychoactive medications that carry with them potentially serious side effects. I think we’re closer to the truth when we envision kids with an ADHD diagnosis as younger than their years, and see that difference as a positive thing.

I discuss this issue in greater depth in my book: The Myth of the ADHD Child, Revised Edition: 101 Ways to Improve Your Child’s Behavior and Attention Span Without Drugs, Labels, or Coercion

This article was brought to you by Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D. and www.institute4learning.com.

Follow me on Twitter: @Dr_Armstrong